I. ἀναγνώρισις

“Gather your strength and listen; the whole heart of man is a single outcry. Lean against your breast to hear it; someone is struggling and shouting within you. It is your duty every moment, day and night, in joy or in sorrow, amid all daily necessities, to discern this Cry with vehemence or restraint, according to your nature, with laughter or with weeping, in action or in thought, striving to find out who is imperiled and cries out.”

- Nikos Kazantzakis, Ασκητική. Salvatores dei

In between the first draft of Moby-Dick and its ultimate form, Herman Melville read through the works of William Shakespeare, an experience that fundamentally altered his writing and contributed greatly to the final shape of his (and perhaps the English language’s) greatest novel. The first draft of Moby-Dick was apparently giving Melville no small amount of trouble, and he complained to a friend that “blubber is blubber you know; tho you may get oil out of it, the poetry runs as hard as sap from a frozen maple tree”.

Shortly before he began writing the novel, Melville had purchased a seven-volume set of Shakespeare’s plays, which theretofore he had not read because other editions had such “vile small print unendurable to my eyes which are tender as young sperms”. This set, however, had “glorious great type” and Melville attacked Shakespeare’s works with relish. Fortunately, history has retained the original set and we can still see Melville’s marginalia across the bard’s writings.

Melville’s love of Shakespeare is apparent in his writing and correspondence, where he talks about Shakespeare’s efforts to uncover something True. The “things that make Shakespeare, Shakespeare”, he wrote, were “those deep fare-away things in him; those occasional flashings-forth in the intuitive Truth in him; those short, quick probings at the very axis of reality.”

Melville would then go on to probe that same axis of reality and, perhaps to his ultimate detriment, uncover something of the Truth.

II. ἀδύνατος

“Some of the words you'll find within yourself,

the rest some power will inspire you to say.”

- Homer, The Odyssey

In his 2019 novel An Orchestra of Minorities, Chigozie Obioma gives us a modern re-imagining of Odysseus by telling the story of Chinonso Solomon Olisa, a young Nigerian chicken farmer who falls in love with a wealthy young woman who he saved from a potential suicide attempt. Ultimately, the two decide to get married, but her family does not approve of Chinonso. He is persuaded to attend university in Cyprus in order to win over her family, and sells his late father’s property and all his prized poultry and tells her that he will return for her hand in three years with a degree.

His arrival in Cyprus turns out as bleak as one might expect—his friend from school has absconded with all his savings, he was not enrolled in the university, and he finds himself without penny or prospect on the non-European side of a strange, desert island. He cannot go home and is too ashamed to tell his fiancée what happened to him, unsubtly ignoring her calls as he befriends some other Nigerians and finds some basic work and accommodation. [Spoilers begin here] He is eventually falsely accused of a horrific crime and spends several years in a violent Cypriot prison. He composes a letter to his fiancée but it is never sent—a friendly guard would help him if she lived in Cyprus, but the postal fee back to Nigeria is simply too high.

Chinonso is eventually released from prison and begins his quest to reunite with his fiancée. He reads The Odyssey and wonders if she was as faithful as Odysseus’s Penelope. He is haunted by memories of prison that he cannot speak of. He mourns the loss of his chickens and his family’s land. He reunites with the man who betrayed him and stole his money, but instead of killing him as planned, the man makes amends and they begin a friendship. The story with his fiancée ends less happily, with Chinonso descending into madness and ultimately committing an act of violence.

This final violence sets us up for the central narrative conceit of the novel, which is that it is being told by Chinonso’s chi (guardian spirit) to Chukwu, the supreme god of Igbo theology. Instead of answering for the actions of its host after his death, the chi has taken the unusual act of “soaring untrammeled like a spear through the immense tracts of the universe”. The novel is the recollection of Chinonso’s chi in the desperate hope to explain the context and backstory of his great crime, so that Chukwu can intervene against the divine retribution owed to Chinonso by Ala, “the great mother of mankind…whose gender or kind no man or spirit knows”.

In The Odyssey, the many sorrows of Odysseus were primarily caused by Poseidon, who was angry at Odysseus for blinding his son Polyphemus (Poseidon was also on the side of the Trojans in the Trojan War). Odysseus inhabits a world where the gods are ever-present and directly impact the action. He angers a god, and thus the plot is set in motion.

In An Orchestra of Minorities, the spiritual world is still always present, but the characters do not necessarily recognize this. Chinonso experiences years of suffering because of his own actions or the actions of other humans. The novel culminates in his great sin that could bring the wrath of the gods, but his struggles are entirely human-wrought. His world is more modern, where the gods are not intervening directly in our lives—theophany must be sought out, must be earned. Though we are left without complete resolution, it is Chinonso’s grief and manic violence that have led him to the judgment throne of God, to Eluigwe, the Heavenly Place. He descended into madness and has ascended toward heaven.

III. ἀλλοίωσις

“The Ibis was not a ship like any other; in her inward reality she was a vehicle of transformation, travelling through the mists of illusion towards the elusive, ever-receding landfall that was Truth.”

- Amitav, Ghosh, Sea of Poppies

On the back flyleaf of the final volume of Herman Melville’s beloved set of Shakespeare, he wrote a curious inscription that would excite Melville scholars for years. He first writes “Ego non baptizo te in nominee Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti — sed in nomine Diaboli” [“I baptize you not in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, but in the name of the Devil”]. In Chapter 113 (The Forge) of Moby-Dick, Captain Ahab recites a condensed, pagan version of this prayer (excluding references to Christ and the Paraclete) as he forges a new harpoon head with which to slay his leviathan. Craving “the true death-temper”, he spurns water and uses the blood of his three harpooners to temper the blade. It is one of the most striking scenes in the novel and, as confessed in a letter to his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, the prayer is the “secret motto” of the book.

The second half of his annotation is perhaps even more interesting: “Madness is undefinable—It & right reasons extremes of one—Not the (black art) Goetic but Theurgic magic—seeks converse with the Intelligence, Power, the Angel." According to Melville, madness and right reason are different extremes in their ability to approach the Divine, a sort of heavenly horseshoe theory. Off this axis lie the black arts—those making Faustian bargains have consigned themselves to perdition, never to see God.

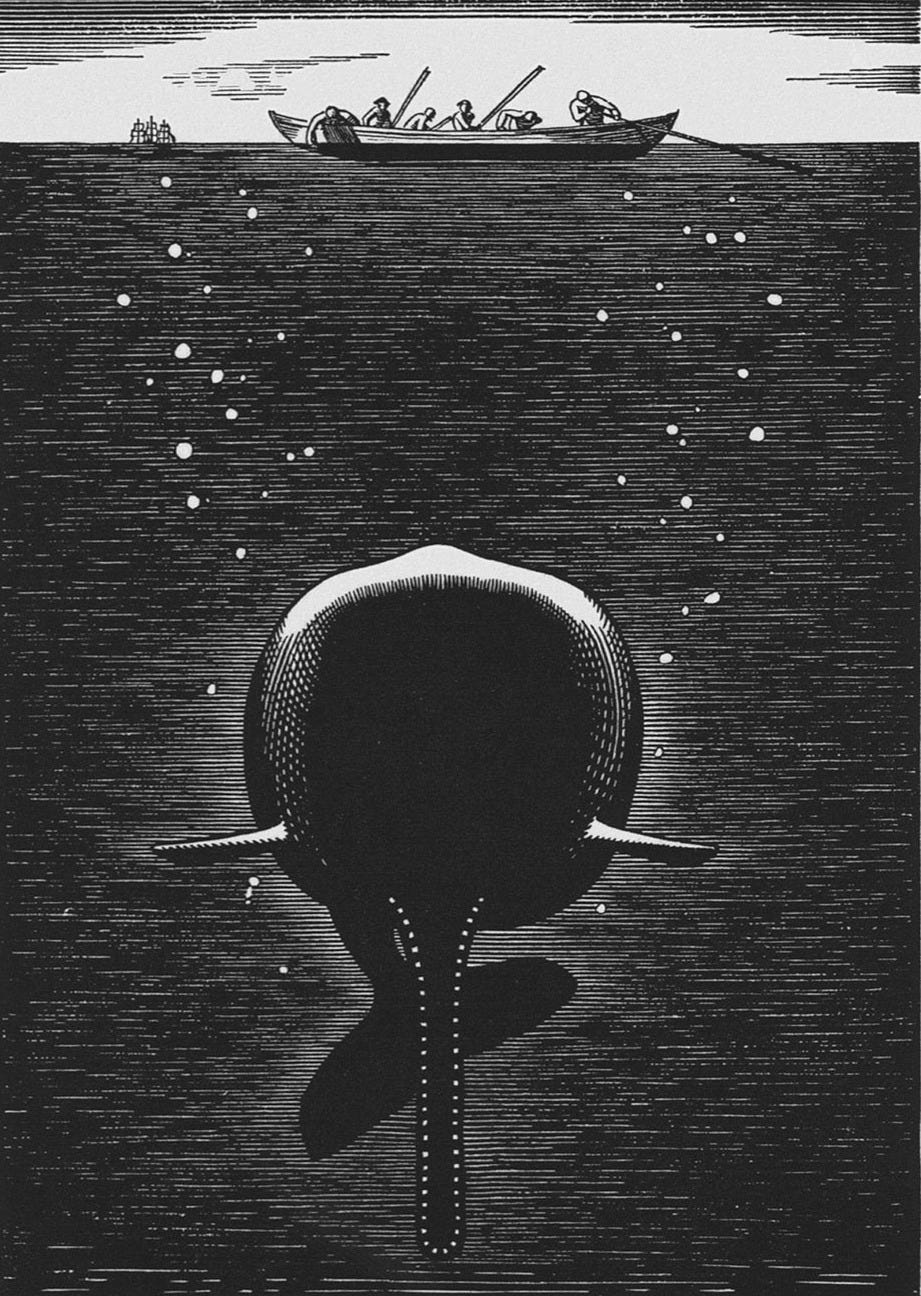

The novel is filled with different characters who embody these approaches to life. Ahab is the obvious example of the black arts, with his blood baptism and countless other blasphemies expressed throughout the narrative. Toward the end of the novel, he has all but resigned himself to his coming fate. His one goal is to face oblivion with his foe, to drown in the depths of the Pacific having killed the great whale he has spent the last 600 pages chasing.

The man of “right reasons” is harder to place, given the general lack of well-balanced crew aboard the Pequod. Some equate this with Ishmael, our mysterious narrator, but this doesn’t seem quite right. The first chapter alone indicates something of an unhinged character, whose humors lead him to join the first ship he can find off Nantucket and sign up for four years of sailing across the world. In his seminal essay Call Me Ishmael, Charles Olson suggests that this man might be the barely-mentioned Bulkington, first seen in the Spouter-Inn in Chapter 3, an “aloof…sober” sailor with a fine stature. He reappears as a crew member on the Pequod, but is never spoken of again after Chapter 23.

Finally, the man of madness (but not the violent Theurgic magic of Ahab) is often identified as Pip, the Black cabin boy who is left to drown in the ocean after he leaps from his boat. He is saved by pure chance, but not after undergoing a fundamental transformation (emphasis mine):

“The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul. Not drowned entirely, though. Rather carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad. So man’s insanity is heaven’s sense; and wandering from all mortal reason, man comes at last to that celestial thought, which, to reason, is absurd and frantic; and weal or woe, feels then uncompromised, indifferent as his God.” (Chapter 93)

From that moment on, Pip walks around “like an idiot”. He ultimately becomes close with Ahab and is able to awaken a sense of humanity in the captain, to reel him back from the utter abyss of madness. It ultimately is not enough to save Ahab from his fate, but the two characters develop a bizarre relationship in the last section of the novel—a mix of the holy fool and the crazed demoniac. He meets God and offers Ahab a final chance at redemption—spurned, they both perish under the waves.

IV. ἀποδίωξις

“I believe I believe I believe I believe

Canaan ain’t far for the souls who barter

Their pain for sweet relief”

- Rainbow Kitten Surprise, “Painkillers”

In Carsten Jensen’s We, the Drowned (2006), the character Laurids Madsen is a gregarious, fun-loving man from Danish island town of Marstal. During the First Schleswig War in the 1840s, he conscripts into the Danish Navy and finds himself aboard a ship that gets blown up. He flies up as high as the main mast and finds himself standing outside the pearly gates, where St. Peter merely “flashed his bare ass at him” and sends him back earthward. Laurids tells this fun story when he reunites with his compatriots, but it soon becomes apparent that something has changed after his encounter with the divine. He longs for the sea and eventually joins another crew and disappears, leaving his wife and four children without an update on his travels or the closure of his death.

The first third of the novel follows the travels of his youngest son many years later, who sails his way across the globe, following the whispered clues of bartenders and criminals until he ultimately meets the shell of the man who was his father. Without giving away spoilers, his father has never truly recovered from his entrance into the foyer of heaven. His son, disgusted, walks away from his father—an ouroboros of mutual abandonment—for what good is a family when one has tasted the ineffable divine, and what good is a father with drunken eyes always casting upwards?

The father’s madness passes down to his son and we see that the aftershocks of the divine can affect multiple generations, can impact an entire town. The years pass, the son becomes older, and the world goes to war. And yet the lingering effects of the father’s moment with the divine linger.

Devotees of saints and sufis, of course, are proof that a mystical experience can ripple throughout the world for centuries, and its impact often leaves the recipient even more exiled from society. What Sunday School child has not drawn a picture of Jonah beseeching God from underneath the waves in the belly of a great fish? St. Francis sparred with God in an Italian cave and ended his life blind and bleeding from his aching, stigmatic hands. Millennia of sadhus have appeared mad to the outside world and found their way, ascetic and strange, to the liminal spaces of divinity.

Melville was no doubt right that madness is a shortcut to God, but every culture seems to have examples of the pitfalls of this path.

V. Θάλαττα

“Love, come and save me from the drowning

Love, go and save him from the drowning.”

- Right Away, Great Captain!, “Love, Come Save Me”

It isn’t without meaning that all the examples of madness involve the sea. The stories in Moby-Dick and We, the Drowned are nautical and the glimpses of heaven and descents from sanity occur mostly asea. In An Orchestra of Minorities, the protagonist travels across the Mediterranean Sea to an island where he metaphorically descends into a hell he never psychologically recovers from. It is also, of course, an explicit homage to that greatest of seafaring epics, The Odyssey.

There is something about the sea that invites madness. Perhaps the isolation, the great vastness, the ineffable and indefatigable nature of it all. What other profession takes a person away from their home for years at a time but leaves them restless until they leave once more? Perhaps because on dry land one loses their connection to the Infinite. Perhaps because, once you have cast out into the Deep, you will never feel satisfied in shallower environs. It seems only right that God chose the apostle exiled to a sea cave on Patmos to reveal his most world-shattering apocalypse, to unveil the pillars of the cosmos to one already gazing at the boundless ocean.

In Moby-Dick, Melville constantly returns to the primal nature of the sea, the mythical world-ocean which existed before all history. He asks why the ancient Persians and Greeks considered the ocean holy, why so many cultures gave it its own deity. In the final chapter mentioning Bulkington (the character who may in fact be finding God through “right reason” in lieu of madness), Melville contrasts the safety of the port—its “safety, comfort, hearthstone, supper, warm blankets, friends, all that’s kind to our mortalities”—and the ship’s need to “fly all hospitality” and avoid striking itself against the shore.

In his final admonition to Bulkington, the narrator gleans “that mortally intolerable truth” that the “wildest winds of heaven and earth” are conspiring to cast man onto the shore, but “all deep, earnest thinking is but the intrepid effort of the soul to keep the open independence of her sea”. In “landlessness alone resides highest truth”. To Melville, then, the man of right reason might find God on the intellectually “treacherous, slavish shore”. Better to avoid the “worm-like” life ashore, with all its safety and comfort, and to strike out into “that howling infinite”, even if it kills you.

Better for the soul to fly into the unknown cosmos, “shoreless, indefinite as God”. The narrator knows upon writing this chapter that Bulkington, for all his right reasons, will die as a result of Ahab’s madness. He will sink with the rest of the crew in a final fight against the demiurge lurking beneath the surface of the novel. And so Ishmael leaves his final mention of Bulkington with this grim note of optimism: “Take heart, take heart, O Bulkington! Bear thee grimly, demigod! Up from the spray of thy ocean-perishing—straight up, leaps thy apotheosis!”